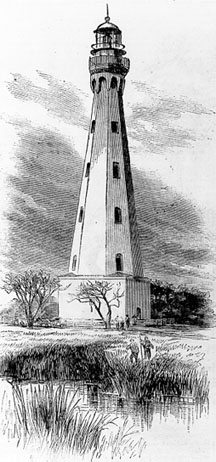

Morris Island Lighthouse

Morris Island, South Carolina - 1876 (1767**)

History of the Morris Island Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2014-07-09.

It's hard to believe that the Morris Island Lighthouse, standing alone in the Atlantic Ocean, off the end of Folly Beach, once contained a large three-story keepers' dwelling, a one-room schoolhouse, and thirteen other outbuildings.

Named after King Charles II, Charles Town, later shortened to Charleston, was established by English settlers in 1670. One of the Lords Proprietors, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, deemed it to become a "great port towne," a mission, in time, it would fulfill.

In 1673, the first light was established at Morris Island. It was nothing more than tar and pitch, burned in an iron basket on the beach. The "fier balls" were maintained by a man hired by the general assembly, and was supported by a small harbor tax paid by ships entering and leaving the port.

By 1700, there were two main channels to reach the inner harbor at Charles Town, the main channel, which ran near Morris Island, and a second channel, which ran near Sullivan's Island. Around 1716, the light keeper on Morris Island started burning tallow candles in place of the "fire" baskets, which later gave way to spider lamps.

By the mid-1700s, Charles Town continued to flourish, and became a bustling hub for Atlantic trade of the southern colonies. By 1750, more than 800 ships a year entered the harbor, mostly exporting Carolina Gold Rice.

That same year, the Commons House of Assembly decided to build a permanent lighthouse, but insufficient funds pushed it out to 1765. However, by order of King George III, due to the ever increasing port traffic, construction of the lighthouse on Middle Bay Island was started on May 30, 1767.

When completed, the structure was described as a "strange building, not over fifty feet high and twenty feet in diameter." Spider lamps, suspended from the dome, burned fish oil.

1767 Charleston Lighthouse

1767 Charleston Lighthouse

Charles Town played a major role in the American Revolution, having repelled a British attack on Fort Moultrie in June of 1776. The city would later fall to the British in 1780 and would be under British control until December of 1782.

By 1783, Charles Town was shortened to Charleston. Several years later, in 1790, the newly formed federal government of the United States took control of all navigational aids, including the Charleston Lighthouse, its one-room keeper's dwelling, and several outbuildings.

During the 18th century, Morrison's Island was made up of three separate small islands. Coming's Island was located to the north, with Middle Bay Island to the south. Around the turn of the century, incoming tides blocked up many of the inlets, which merged the three islands into one. Its name was later shortened to Morris Island.

Congress appropriated $5,950 for the Charleston Lighthouse in May of 1800. The following year, the tower was rebuilt, and the height increased to provide better visibility.

The cotton plantations of the post American Revolution period fueled much of Charleston's growth and would take it into the 1820s. Around that time, the consensus around the state was that its laws were superior to those of the Federal Government. These feelings continued to escalate over the years.

In 1858, the lighting apparatus inside the Charleston Lighthouse was upgraded to a first-order Fresnel lens. The light wouldn't shine long, as the first shots of the Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor during the early morning hours on April 12, 1861.

With the onset of the Civil War, most navigational beacons of the south were darkened for fear of their use by Union troops. When it looked as though the location would fall, retreating Confederate troop were instructed to destroy the assets.

In port towns and along the seaboard, lighthouses were highly valued. Like the Cape Lookout Lighthouse in North Carolina and the Hunting Island Lighthouse in South Carolina, the Morris Island Lighthouse was destroyed during the Civil War.

By 1870, a new set of range lights was established to guide vessels through the Pumpkin Hill Channel. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for 1870 had the following entry:

Morris Island range-lights, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina - The two beacon-lights authorized to be placed on Morris Island, to serve as a range for the present deepest channel, known as the Pumpkin Hill Channel, have been completed, their lights exhibited, and the Rattlesnake Shoals light-vessel restored to her proper position off Rattlesnake Shoals.

Within two years, the lack of a first-order lighthouse at Charleston left a dark area along the coast between Cape Romain and Hunting Island. It became evident that the range lights served their purpose very well, however, they were no substitute for a sea coast lighthouse. As continuous shoals from Cape Romain to River Saint John extend out from the mainland as far as seven miles, the lives and cargo of passing vessels were endangered.

The Lighthouse Board advised that the only way to combat the problem would be to establish a sea coast lighthouse, or through the use of light vessel, which they deemed cost prohibitive. As the current rear range lighthouse at Charleston lacked the height of a sea coast lighthouse, they recommended a new first-order tower, with a height of 150 feet, be erected. The estimated cost of the lighthouse was $85,000.

An appropriation of $60,000 on March 3, 1873, provided the funding necessary to get the lighthouse started. The Lighthouse Board had recommended the tower be placed on the location of the original Charleston Lighthouse, which was on land already owned by the government.

A contract for the iron lantern of the tower had already gone out to bid, and a contractor was selected. The foundation work was scheduled to start in the fall, as the summer was deemed the "sickly season" due to malaria outbreaks. That year, an additional appropriation of $60,000 was requested.

A location, 1,700 feet north and 60 degrees east of the Pumpkin Hill rear range lighthouse, was selected. This location, when matched up with the front beacon, formed a range through the Northwest Channel, which was known to have the deepest water. By 1874, a wharf for landing men and materials, a storehouse, and quarters for the workers were established.

To easily move materials between the location and the site, a tramway was set up. Test borings in the soil showed that to get to coarse sand, the piles would need to be driven to a depth of at least 50 feet. It was decided that a pile and grillage foundation would be used, with the pilings driven to different depths depending on whether they were outer or inner pilings.

Also in 1874, a contract for the metalwork was executed, and the pieces were ready for delivery. The massive first-order lens was also purchased. Like the previous year, work could not be carried out during the summer months due to frequent malaria outbreaks, so it had to be put off until fall. Finally, that year, a final appropriation of $30,000 was requested to complete the tower.

The following year, most of the foundation work was complete. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for 1875 had the following detailed description of the foundation:

338. Morris Island, (main light,) on south end of Morris Island, South Carolina - At the date of the last annual report, seventy-nine of the foundation-piles had been driven. Owing to the unhealthiness of the climate at this station the work had to be suspended during the remainder of the summer. Operations were resumed in November, and the piling completed. The piles were then cut off, three feet below the level of the water, and capped with 12 by 12 inch timbers, forming the grillage. The space between the timbers, and for three feet below them, was filled in with concrete, which was extended two feet outside of the outer row of piles. The base of the tower below the surface of the ground is composed of concrete, 8 feet thick, reduced by offset courses to a surface base of 36 feet in diameter. This has been completed, and is now ready for the brick superstructure. The metal-work of the tower, with the exception of a small portion lost by the sinking of a lighter, has been received at the station and stored ready for use. The missing portions are being duplicated by the contractor. Arrangements have been made for delivering the brick for the tower, and the work will be resumed in the autumn. It is expected to complete the tower during the spring of 1876.

By 1876, most of the station was completed at a final cost of $149,993.50. The entry in the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for that year sums it up best:

352. Morris Island main light, on the south end of Morris Island, entrance to Charleston Harbor, South Carolina - At the date of the last report the foundations of the tower had been completed and the work suspended during the unhealthy season. Operations were resumed in October, 1875, when the work on the superstructure was commenced and has since been steadily continued to completion. The illuminating apparatus, a first-order lens, fixed white, with an arc of 270, and a catadioptric reflector of 90, has been set up. The oil and work rooms have been built, and the tower is ready for lighting. The keeper's dwelling has been commenced and is nearly completed. Cisterns of an aggregate capacity of 7,000 gallons have been built. The ground in the vicinity of the tower, originally nearly on a level with the adjoining marsh-land, and subject to overflow at spring-tide, has been raised to an average height of 3 feet over an area of 300 by 200 feet, with sand hauled from the site of the old tower (the nearest available point) and covered with the soil excavated from the foundation. The easterly side bounded by the marsh has been protected from the tides by a timber and plank scarp faced with the debris of the old tower. Examinations and soundings of the southeast and Pumpkin Hill channels, with a view of determining whether it is necessary to retain the present range-beacons, have been made.

The design of the Morris Island Lighthouse is very similar to the Currituck Beach and Bodie Island Lighthouses in North Carolina. It was officially designated as the Charleston Main Light, and was lit for the first time on the night of October 1, 1876. It wasn't given its unique paint scheme until 1878, alternating black and white bands, to allow the brickwork to dry.

When the station was completed, it was so large that it formed a small community. The three lighthouse keepers and their families, lived in a large three-story keeper's dwelling. By the late 1800s, there were 15 buildings at the station, including the keeper's dwelling, several out buildings, and even a one-room schoolhouse for the children, with a teacher being brought over to the island during the week.The Chamber of Commerce in Charleston petitioned Congress in October 1877 for funds to construct jetties, designed to deepen the channel into Charleston Harbor. Construction of rubble-mound jetties started in September of the following year and would take place over the next fifteen years. When completed, the north jetty was 2.91 miles, and the south jetty was 3.61 miles in length.

As early as 1881, while the jetties were still under construction, the main channel began to deepen. But that was not the only transformation going on, nearby Morris and Sullivan's Islands began to rapidly erode. To try and counteract the effects of the erosion, spurs were added to the north jetty which corrected the erosion problems for Sullivan's Island. Although designed, spurs were never funded for the south jetty, leaving Morris Island to erode.

A category 2 hurricane on August 25, 1885 would cause extensive damage to the Charleston area and the Morris Island Lighthouse. A brick wall that surrounded the station was partially destroyed, the boathouse was overturned, plank walkways between the buildings were carried away, and the Morris Island Range Lighthouses were destroyed.

Remediations were performed that year with the range beacons being re-established on August 28. Five new pilings were installed and the boat house righted, the bridge over the creek was rebuilt, and plank walkways were re-established.

Almost one year later, on the night of August 31, 1886, a powerful earthquake struck the Morris Island Lighthouse. It would later be known as The Charleston Earthquake of 1886 and, as the Richter scale wasn't developed until the 1930s, it was estimated to be between 6.6 and 7.3 on the Richter scale.

The earthquake caused extensive damage to the station, throwing the lens out of position, sending several cracks spiraling down the tower, and leaving the lighthouse with a noticeable lean towards the ocean (see picture above). Engineers from the Lighthouse Board confirmed the slight seaward list and that the cracks did not endanger the stability of the tower. The lens was replaced, and broken parts were repaired as soon as possible.

Many changes occurred over the years. A post light was added in 1889 to act as a front range light, while the Morris Island Lighthouse was used as the rear range. In 1890, a new 12' x 14' oil house was built on the property.

After moving and rebuilding the front and rear beacons around Morris Island for many years, the Charleston (Morris Island) Range Lighthouses were finally discontinued in 1899, leaving only the Morris Island Lighthouse on the island.

1876 Morris Island Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

1876 Morris Island Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Erosion of the island continued. In 1880, the lighthouse was 2,700 feet from the shoreline and by 1938, the shoreline was at the base of the tower. On June 22, the tower was automated and the first-order Fresnel lens was removed.

To reinforce the tower, the Army Corps of Engineers built a sheet steel bulkhead around the base of the tower, and filled it with reinforced concrete. For fear that the structures on the island would wash away with the tides creating hazards for mariners, they were removed.

The keeper's dwelling was purchased by Dr. Richard Prentiss for $55. Crews disassembled the structure and moved the materials to Edisto Island, where they were used to build two houses. The houses were later destroyed in a storm.

During World War II, Naval Aviators were trained by dropping live bombs on abandoned houses at the northern end of Folly Beach. The Morris Island Lighthouse, being in close proximity, sustained damage to the concrete base from the repeated blasts.

By 1948, the Morris Island Lighthouse's importance was diminishing due to a Loran (LOng RAnge Navigation) station being established on Folly Beach. With this station, ships were able to pick up the signal more than 100 miles out to sea, which would safely guide them into the Charleston Harbor.

Due to the constantly shifting sands, by 1956, the Morris Island Lighthouse was too far off the shipping route. The Coast Guard started drawing up plans for a new lighthouse, which would be located on the northern side of Charleston Harbor, on Sullivan's Island.

After storing the first-order Fresnel lens since its removal in 1938, the Coast Guard originally planned to auction it off. It later decided to give the lens to the South Carolina Department of Parks and Recreation to use as a museum piece at the Hunting Island Lighthouse. The lens still resides there today.

On June 15, 1962, the light at Morris Island Lighthouse was extinguished, and the light of the new Sullivan's Island Lighthouse took over. The Coast Guard had made plans to demolish the Morris Island Lighthouse in 1965, allocating $20,000 for the work.

Residents of Charleston petitioned their state senators and flooded their offices with letters. Although the Preservation Society of Charleston attempted to gain ownership of the historic structure, it did not have a financial resources to maintain it. The group contacted the National Park Service about ownership, but they declined.

Although the group was unsuccessful in finding an owner for the structure, it did succeed in stopping the demolition. The property was instead turned over to the General Services Administration to be auctioned off.

The lighthouse, 421 acres of submerged property, and 140 acres of dry land were auctioned off. After the 23 bids were received, John Preston Richardson was the winner with a bid of $3,303.03. Although he had planned to preserve the tower, upon inspection, he was shocked at the level of disrepair.

Mr. Richardson offered to donate the lighthouse to the city or the state, if they agreed to construct the spur jetties to protect the island. Neither group was interested and within four months of owning the property, the lighthouse was again for sale.

A group of local realtors purchased the entire 820 acres of Morris Island in 1966, with the exception of the lighthouse and a small tract of land. One of the realtors, S.E. "Speedy" Felkel, purchased the lighthouse and land a month later for $25,000.

Although "Speedy" Felkel owned the lighthouse for thirty years, he never developed it. As it was used for collateral on a loan which was defaulted on, the lighthouse was put up for sale in 1996 by the creditor, Paul Gunter.

A group called Save The Light, Inc. was formed and purchased the lighthouse in February 1999 for $75,000. Save The Light, Inc. through the Heritage Trust program, worked to transfer ownership of the Morris Island Lighthouse to the state.

On April 21, 2000, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources voted to take ownership of the lighthouse, which was officially approved on December 13, 2000. The tower was leased back to Save The Light, Inc. that same year to allow the fundraising and preservation efforts to continue.

Phase 1, which provided lighthouse stabilization, took place in May of 2007. During this phase, a new cofferdam was installed around the tower to provide protection from the sea. The work was completed in March of 2008 at a cost of just over $3 million.

The second phase, which built upon the work of the first phase, was to install new concrete micro-piles under the foundation and fill the cofferdam with sand to provide additional stabilization. Phase 2 was completed on July 31, 2010 at a cost of just under $2 million.

Future phases of the restoration focus on restoration of the lantern, the tower, and construction of a viewing platform and history kiosk on Folly Island.

Today, the lighthouse bears a unique daymark of red and white bands, but this was not always the case. The tower originally had a black and white stripes, very similar to the Bodie Island Lighthouse in North Carolina. Over the years, the black bands captured the heat from the sun. Over time, the paint flaked off, leaving the natural brick color of red.

Due to the continual erosion, to date, the Morris Island Lighthouse stands more than 1,600 feet offshore.

Reference:

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- Lighthouses of the Carolinas - A Short History and Guide, Terrance Zepke, 1998.

- A History of South Carolina Lighthouses, John Hairr, 2014.

- Save The Light, Inc. website.

- The Morris Island Lighthouse: Charleston's Maritime Beacon, Douglas W. Bostick, 2008.

Directions: The lighthouse sits off shore. Take state route 171 into Folly Beach. Once in Folly Beach, take East Ashley Drive to the end. At the end, you can park your car along the road, and walk the half mile out to the beach. From the beach, with a telephoto lens, you can get a pretty good picture of the lighthouse.

Access: The lighthouse is owned by the state of South Carolina. Grounds open, tower closed.View more Morris Island Lighthouse pictures

Tower Height: 161.00'

Focal Plane: 158'

Active Aid to Navigation: Deactivated (1962)

*Latitude: 32.69500 N

*Longitude: -79.88300 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.