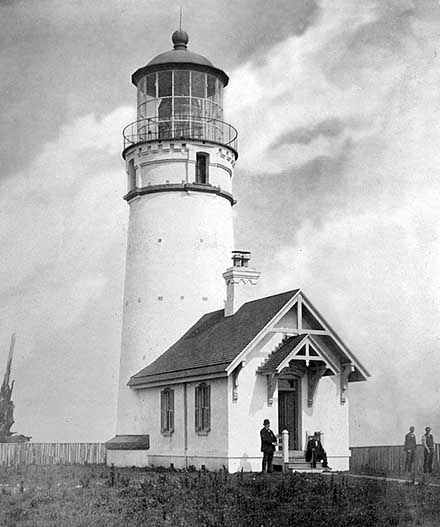

Cape Blanco Lighthouse

Port Orford, Oregon - 1870 (1870**)

History of the Cape Blanco Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2017-06-06.

Oregon's rugged Pacific Coast has many unique features, none more so than Cape Blanco, Oregon's westernmost point. Atop the 200-foot-tall chalky-white cliff stands the Cape Blanco Lighthouse.

Most say the name Cape Blanco comes from Captain Martín de Aguilar, commander of the ship Tres Reyes, which took part in an expedition led by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1603. The expedition was to search for usable harbors and the mythical city of Quivira, or the "Seven Cities of Gold." His ship logs contain one of the first written descriptions of the Oregon Coast.

While on the expedition, a storm had separated the two vessels. Vizcaíno's vessel made it as far as the California-Oregon border, while Aguilar's vessel was said to have made it as far as Coos Bay. It was on January 19, 1603, that he spotted the cape and provided the name Cape Blanco de Aguilar. While returning to Mexico, Aguilar and most of his crew died of scurvy.

More than 150 years later, Spain sent out a Portuguese explorer and navigator named Bruno de Heceta from San Blas, Mexico with two vessels, a 45 man crew, and provisions to last a year. While on this expedition, de Heceta's second lieutenant, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, in command of the Sonora, named the headland Cabo Diligensias, a name that never really stuck.

British naval Captain George Vancouver explored the area in 1792 and named the point Cape Orford, for George, Earl of Orford, who he deemed "a much-respected friend." Although this name was used for some time, the Cape reverted to the name given by Aguilar in 1603 but was shortened to Cape Blanco.

The Orford name would not be lost. The name would be used in 1851 by Captain William Tichenor, who had established Port Orford, a settlement five miles south of Cape Blanco. When gold was discovered along the sandy beaches in 1853, it drew in thousands of settlers to Port Orford. A bustling seaport soon formed to offload supplies and passengers for the new town.

The first lighthouse erected on the West Coast was the Alcatraz Island Lighthouse in 1854. A few years later in 1857, the Umpqua River Lighthouse was erected in Winchester Bay, Oregon, and in 1866, the Cape Arago Lighthouse was established.

As trade along the West Coast continued to grow year over year, the Lighthouse Board was looking to fill in many dark areas and mark the dangerous reefs along the Pacific Coast of Oregon. By the late 1860s, the Lighthouse Board had identified Cape Blanco to fill in the gap between the Battery Point Lighthouse in California and the Cape Arago Lighthouse in Oregon. It would also serve to mark the Orford Reef, a navigational danger in the shipping lane between Cape Mendocino and Point Greenville.

The federal government purchased the 47-acre headland from John and Mary West in 1867. By 1868, the deed had been transferred, but it was noted that the only access to the cape was via the adjoining private property, which the Lighthouse Board had noted had materials for making and burning bricks. Therefore, the board had purchased a right of way with the privilege of taking water, sand, clay, and wood.

By 1869, due to an abundance of trees, the land had been cleared to prevent them from being blown down during excessive windstorms that frequented the areas, as well as to prevent any encroachment from a forest fire. An added bonus was that it diminished the amount of fog in the area.

The entry in the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for 1869 noted that "much money could be saved, if brick could be made at the cape instead of bringing them from San Francisco." Therefore an agreement was made to source bricks locally at $25 per one thousand bricks, which was about one-third of the transportation costs to bring bricks from San Francisco.

Cape Blanco Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Cape Blanco Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

The first batch of bricks was made in the fall of 1868 and was of acceptable quality. The second batch, made in the spring of 1869, was rejected due to poor quality. The construction, supervised by Lieutenant R. A. Williamson of Army Corps of Engineers, was completed in 1870.

Once the tower was erected, all other materials, such as the lens, had to come by sea. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for the year 1870 documented the hardship:

Cape Blanco, sea-coast of Oregon - The light-house structures at this point are in progress, and will be completed by December 15 of this year. This point can only be reached with materials and labor by sea, and, after reaching the offing, they can only be landed under the most favorable circumstances of sea and weather through the surf. Freights for this section were held at fabulous prices by owners of vessels, rendering it necessary to burn the brick on the ground, which was successfully done; but all other materials and provisions for the mechanics had to be sent by sea, and landed at great risk of loss of life and property.

The Cape Blanco Lighthouse, since its inception, was meant to be a primary seacoast light, as there is no harbor in the vicinity. When completed, the white masonry tower stood 59 feet tall and housed a first-order Fresnel lens sourced from Henry-Lepaute of Paris, France. With a focal plane of nearly 260 above mean sea level and 45,765-candlepower, the light was visible for nearly 21 miles at sea.

Attached at the base of the tower was a brick workroom measuring 15 feet 6-inches by 23 feet. The interior of the workroom was divided into two separate rooms. The north room was used to store lard oil while the south room was used as the workroom.

For the keepers, a two-story T-shaped brick duplex was erected. The same design would be used two years later in the residence at the Yaquina Head Lighthouse. One side was provided for the principal keeper and his family, the other side was shared between the two assistant keepers and their families. After 1900, the front porch was enclosed due to the harsh coastal weather.

The Pacific Coast: Coast Pilot of California, Oregon, and Washington for the year 1889 had the following description of the Cape Orford (Cape Blanco) Lighthouse:

This is a primary sea-coast light. The light-house is situated on the highest part of Cape Orford, from which the heavy trees were cut when the buildings were erected. It is nearly two hundred yards inside the western pitch of the cape. The tower is the frustum of a cone, and is built of brick painted white. The dome of the lantern is painted black. The keeper's dwelling is a two-story brick building, painted white, with green window blinds; it is situated about thirty-five yards southward of the tower. The light is a fixed white light of the first order of the system of Fresnel. It was first exhibited on the 20th of December, 1870, and shows every night from sunset to sunrise.

Given that Cape Blanco sits nearly 1½ miles out in the Pacific Ocean, the point regularly sees winds top 100 mph. In each instance of the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for the years dated 1877 to 1880, there were instances of repairs to the dwellings due to wind damage. Reported in 1879, it was noted that the east half of the south gable was torn off the keeper's dwelling and in 1880, it was reported that the south side of the dwelling was reshingled. That same year, it was reported that the shutters on exposed sides were made solid to protect against "gravel squalls."

In September 1884, a new barn, 45 by 20 feet in-plan was built. That same year, the Lighthouse Board requested $2,000 to purchase the right of way to this station. The only access to the town of Port Orford was along the beach, which could only be traveled at low tide and was like quicksand. The request was approved as the following year, it was noted, "A road 7,000 feet long was built from the station to connect with the road leading to Port Orford, the nearest landing and post office."

Erosion of the bluff was a constant concern. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board had the following entry in 1887:

To prevent sliding and caving of the bluff bank of the narrow ridge connecting the station with the mainland, wooden box drains were placed in the main ravines and branching gullies, the banks were graded to natural slopes, brush shoots were transplanted on the slopes and along the tops, and grass seed was sown over the whole surface. A fence of barbed wire was built around the reservation to exclude cattle.

The following year, a barbed wire fence was erected at the foot of the bluff to keep livestock from grazing on the vegetation planted on the slope. In 1888, a fence was built around the spring just east of the dwelling to keep the cattle from it and additional grass seed was sown over the bank to keep it from sliding.

That same year, the lard oil lamps were replaced with mineral oil, which burned brighter and was more efficient. The downside was that mineral oil, also known as kerosene, was more volatile and therefore not allowed to be stored in the tower. To rectify this situation, supplies for two oil houses were shipped to the site in 1889 and erected the following year.

Problems with the wagon road to town were frequently noted. The Annual Report of Lighthouse Board for 1890 talked about a storm of "unusual severity" that damaged the outhouses, fences, and the road:

Over two hundred trees which had fallen were removed from it; several land-slides were cleared away and the culverts and bridges were put in good condition, and it is now in fairly good order.

From the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for 1892:

863. Cape Blanco, seacoast of Oregon - The wagon road was put in good order by cutting out fallen timber, grading out slides, and corduroying some 300 feet of its surface. A new storage shed was built in place of the old one, and various repairs were made.

From the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for 1893:

889. Cape Blanco, seacoast of Oregon - During December, 1892, a number of trees fell across the road leading from the county road to the light station. These were removed in January, 1893, and communication was reestablished with the station. A part of this road along the side hill, about three-fourths of a mile from the station, covered with corduroy, has been sliding for some time, until now it has reached a condition where repairs are absolutely necessary. These will be made before the rainy season sets in.

By 1897, the Lighthouse Board was noting how the quarters were insufficient for the three keepers and how they could not be altered to meet their needs. They recommended a new dwelling be erected, not to exceed $4,500, and recommended that Congress appropriate the amount.

The same request was repeated year after year until 1906 when the cost estimate was raised to $5,000. Finally, in 1909 the balance of acts of March 4, 1907, and May 27, 1908, was applied to the construction of dwellings for 30 stations, one of which was for the Cape Blanco Lighthouse.

Constructed was a one and one-half story Colonial Revival Style residence, rectangular in plan with a rear ell section, which housed the bathroom. Hip dormers projected from the front and rear of the gable roof. The principal keeper most likely resided in the new dwelling while the two assistants shared the duplex.

In 1914, the fixed white light was changed to flashing. Its characteristic was a two-second eclipse, followed by three seconds of light, followed by another two-second eclipse, followed by thirteen seconds of light. The pattern would then repeat.

By 1930, a radiobeacon was established at the Cape Blanco Lighthouse. Using its characteristic of three dashes followed by one dot, it allowed ships with radio direction finding systems to determine their location relative to the lighthouse. According to government records, this beacon was operational until 1984.

Cape Blanco circa 1936 (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Cape Blanco circa 1936 (Courtesy Coast Guard)

The station received electric power in 1936. At that time, the first-order Fresnel lens was replaced with a second-order Fresnel lens, which was rotated by an electric motor. Using an incandescent bulb, the candlepower was increased to 320,000. Both the motor and lens are still in use today.

During World War II, the station was taken over by the U.S. Army and used as a headquarters for coastal defense against a possible invasion by the Japanese. An observation deck used for sighting enemy vessels was erected near the southern end of the cape. Although no foot invasion ever took place, an aerial assault was launched from the deck of the submarine I-25 off Cape Blanco.

Before dawn on September 9, 1942, Chief Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita launched his seaplane. His mission was to drop two 170-pound incendiary bombs into the dense forest, with the intention of setting a large forest fire. The fire was to be a retaliation of Colonel Jimmy Doolittle's "30 Seconds over Tokyo" raid earlier that year.

It was hoped that the fire would cause fear and panic, but rain and fog had enveloped the Oregon Coast that morning preventing the fire from spreading. The fire was quickly spotted by a lookout, which dispatched a fire crew to extinguish the flames. Another attempt was made a few months later near Port Orford, but it too waned.

In the 1950s, the Coast Guard altered the station to fit their needs. They upgraded the radiobeacon equipment to Loran (Long Range Navigation), built new barracks, a signal and power building, a garage, storage building, transmitter, and a four-plex.

The 1960s saw additional buildings erected. These included a rheostat building, additional barracks, new radio towers, a masonry garage, water treatment building, a duplex, and a pump house.

In 1990, a portion of the original lighthouse reservation was transferred to the National Parks Service. The National Park Service then deeded a section to the Oregon State Parks and Recreation Department for use as a state park, which was then included in the 1,895-acre Cape Blanco State Park.

In an effort to return the land and the light station to its original state, many of the non-historic buildings constructed during the 1950s to the 1980s were razed. Today, a duplex, garage, electronics building, and radio signal equipment are all that remain from that period.

The only historical buildings that remain are the tower with attached workroom and two cisterns - one dating from 1895 and one from 1909.

The Cape Blanco Lighthouse was automated in 1980. In preparation for turning the lighthouse over to the Oregon State Parks and Recreation Department, the Coast Guard carried out a $15,000 restoration of the tower in the early 1990s.

On November 18, 1992, just after the restoration was completed, vandals broke into the lighthouse through one of the windows. As they ascended the tower, using a crowbar, they smashed every window. Once in the lantern, they again proceeded to smash every window.

The vandals then set their sights on the second-order Fresnel lens where they knocked out one of the circular bull's eyes and several of the smaller prisms that help focus the beam of light. As the lighthouse was owned by the Coast Guard, it was deemed destruction of federal property, and by early December 1992, the case was turned over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

On January 21, 1993, two teenagers were charged by a federal grand jury with vandalizing the Cape Blanco Lighthouse. The damage was estimated at $26,000. After a nationwide search for someone qualified to repair the historic lens, the Coast Guard found Hardin Optical in nearby Bandon, Oregon.

Larry Hardin, President of Hardin Optical, considers the lens one of the optical masterpieces of the 19th century. A $19,250 contract was soon made between the Coast Guard and Hardin Optical to repair the damage. Although Hardin considered the work about a seven in difficulty, he said: "it ranks about a 10 in romantic appeal to me."

Although the lighthouse was placed back into service immediately, one point of the rotation was dimmer due to the damage. As there were no blueprints to work from, Hardin Optical had to design the replacement pieces and rework its machinery to grind and polish the glass. Due to the intricacy involved, it took about two years to recreate and install the replacement pieces.

The work was so good that Coast Guard Chief Ken McLain said: "The replacement parts can't be distinguished from the originals."

The Cape Blanco Lighthouse received a paint job in early 1997. The American Lighthouse Restoration Company performed the work. While there, they also re-glazed the windows and repaired a ventilation system that no longer worked.

In September 2002, the second-order Fresnel lens was removed from the tower to undergo restoration, which was again carried out by Hardin Optical. This work was funded by the Bureau of Land Management as part of a $220,000 restoration, which restored the tower in the spring of 2003. Just after Memorial Day 2003, the restored lens was returned to the tower, and the tower was reopened to visitors.

Today, the tower and grounds are open to visitors April through October.

Reference:

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- Lighthouses of the Pacific Coast: Your Guide to the Lighthouses of California, Oregon, and Washington, Randy Leffingwell, 2000.

- Oregon's Seacoast Lighthouses, Jim Gibbs & Bert Webber, June 2003.

- National Register of Historic Places, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Various.

- The Oregon Encyclopedia website.

- United States Lighthouse Society website.

- Cape Blanco Heritage Society website.

- "Lighthouse Vandals Now Sought By FBI," Times Staff, The Seattle Times, December 8, 1992.

- "Two Teens Charged In Lighthouse Vandalism," Times Staff, The Seattle Times, January 22, 1993.

- "Turns Out Expert Needed To Fix Lighthouse Was Under Their Nose," Times Staff, The Seattle Times, January 31, 1993.

- "Lens Restored In Historic Ore. Lighthouse," Times Staff, The Seattle Times, January 29, 1995.

- "Nobuo Fujita Bombed U.S. In WWII,"" Times Staff, The Seattle Times, October 2, 1997.

- "WW II Japanese Pilot Plants Tree Of Peace At Ore. Bombing Site," Times Staff, The Seattle Times, September 13, 1992.

Directions: The lighthouse is located at the end of Cape Blanco Highway in Cape Blanco State Park. Cape Blanco State Park is located about six miles north of Port Orford.

Access: The lighthouse is owned by the Coast Guard and managed by the Bureau of Land Management. Grounds and tower are open in season (April through October). The Cape Blanco Heritage Society runs the tours.

View more Cape Blanco Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 59.00'

Focal Plane: 245'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 42.83700 N

*Longitude: -124.56365 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.